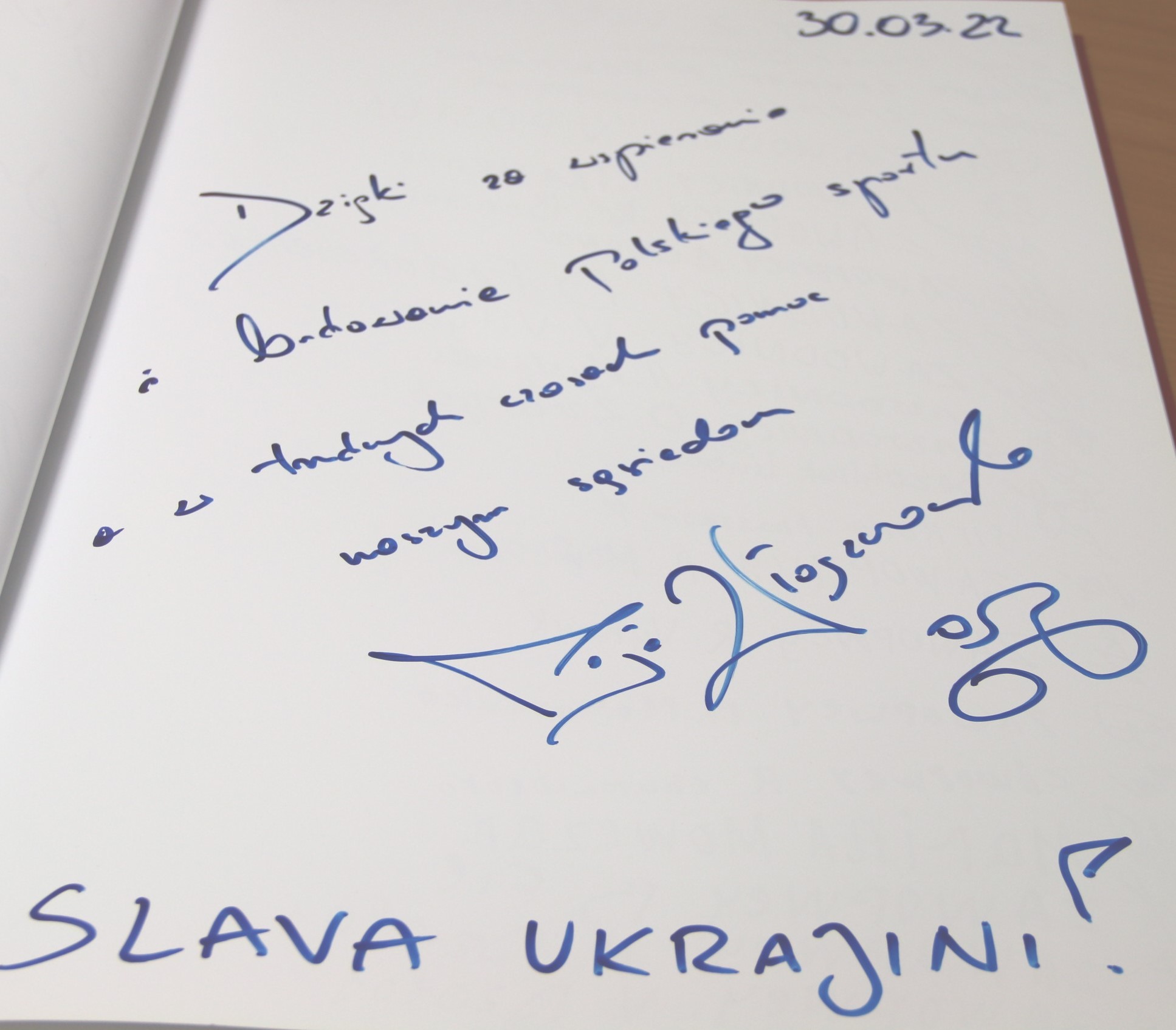

Interview with Waldemar Wendrowski, director of the Central Sports Centre in Spała

How did the Central Sports Centre in Spała react to the news of the outbreak of war in Ukraine?

I probably won't say anything original, but this news came as a shock to everyone working at our centre. Every year, many athletes from all over the world come to us. Not far from Spała, in Tomaszów Mazowiecki, there is an ice rink where the speed skating world cups are held. Our guests included athletes from Russia and Belarus. We knew these athletes, and while it is sad that they will no longer compete with us on the ice, I believe that representatives of the aggressor should be excluded from all games and competitions, with no exceptions.

The centre was quick to get involved in helping Ukrainian athletes.

For the Central Sports Centres in Spała, the trigger for action was a signal from the management that, at the request of Minister Kamil Bortniczuk, made all resources available to help Ukrainian athletes. We were probably the first of all 7 Central Sports Centres in Spała to welcome athletes from Ukraine. At that time, Paralympic archers were returning from Dubai. Flights over Ukraine were already suspended, so a group of 16 athletes landed in Warsaw. Three of them reached our centre – two women in wheelchairs and a man without a leg: Serhiy Atamanenko, world champion in archery. He only stayed with us for a week, but we became friends with him because he is a very interesting person. When he left for Ukraine, he said something that stuck in my memory: ‘I can't run, I can't drive a car, but I can shoot, so I'll definitely be useful there’. When he got home, he called to thank us and invited us to his place as soon as the war was over. One of the women who stayed with us left for Italy after a dozen or so days. During her stay, we provided her with full care and training opportunities – I think we were up to the challenge.

Not long after, we welcomed a group of 26 cyclists from the Kharkiv area, aged between 13 and 17. Three coaches who were over 70 years old came with them. They stayed with us for about 100 days. It was a difficult experience for them. In traumatic circumstances, the kids had to cope with equipment shortages, continue training and learn remotely. We set up a room for them where they had a comfortable learning environment. This group came to us in several passenger cars. During the escape from Kharkiv, two of them were shot at, and we should thank God that no one was hurt. The children, however, were deeply affected, and it was clear that they were shaken. We helped them as much as we could. Our extensive physiotherapy and medical facilities were at their full disposal. We also tried to provide them with the equipment they needed for training. We were helped by the coach of our road cyclists, Andrzej Tolomanov, a Ukrainian who has lived in Poland for 30 years. At the time, he was at a training camp in Spain, and from there, he returned at his own expense to take care of the Ukrainian cyclists living with us. He took many athletes forced to leave their homeland under his roof, provided them with the necessary equipment and organised their stay in places where they could develop. The help of Mieczysław Nowicki, president of the Society of Polish Olympians, was also invaluable, as he obtained a dozen or so bicycles and got the Polish Olympic Committee interested in the welfare of these young cyclists.

How important was it for the Ukrainian athletes to continue training in this extraordinary situation?

I think it was important for them to be able to continue their sporting development and, at the same time - by competing in sports - to prove that Ukraine is not giving up. I saw great determination and drive in both the athletes and the coaches. The young cyclists were actively training, taking part in the race in Krynica, going to the hall in Łódź – they were constantly on the move. It was a smart move on the part of the coaches, because kids need to be shown goals that are tangible and achievable. I think it helped them tremendously during this extremely difficult time.

Our Polish sporting community was sympathetic and open to athletes from Ukraine. Sometimes, the sharing of training facilities caused logistical problems, but it never crossed anyone's mind to complain for that reason. I also saw that many friendships were formed at the school of athletic excellence, where the beach volleyball players trained.

Did the Olympic atmosphere at the centre help the Ukrainian athletes, especially the youngest ones, to face the trauma of the war in their homeland?

Yes, very much so. Ukrainian visitors told us how impressed they were with the centre, the people, and the walls full of surnames of prominent Olympians. I haven't heard so many compliments about the centre for a long time! For us, the people working at the Central Sports Centres and the Polish athletes, this is nothing unusual. We are used to it. This comprehensive care for the athletes – food, regeneration and physiotherapy facilities, training conditions – wowed our guests.

Spała is a small village with 400 inhabitants. In the first months after Russia's invasion of Ukraine, there were more than 700 people here who had been forced to flee the war, so the population almost doubled. Nevertheless, we managed to organise everything smoothly. I think the atmosphere here stimulated the sporting ambitions of the Ukrainian athletes. We were impressed by their incredible determination and will to fight. They did not give up. They channelled their emotions related to the war into dedication to sport. Anger and rage arose in them when they heard more and more about the discovery of mass graves. Channelling emotions is, after all, one of the basic functions of sport. The young Ukrainian sportsmen and sportswomen were proud of their origins, displaying the national colours at every turn – this was a way of demonstrating their loyalty to their homeland. They wanted to show that they were very capable and could achieve a great deal in sports competitions.